I’ve never been able to meditate. I’ve tried it before, frustrated and envious of those people who can sit still and completely disengage from the distractions around them. For a start, I can’t even sit up straight without getting uncomfortable. I know you can meditate lying down, but then I just fall asleep. If I finally do find a comfortable position, I inevitably can’t stop thinking. “Focus on breathing”, all the books and videos say, and I focus on the first three inhalations wonderfully, but soon my mind wanders to my shopping list, deadlines, or reminding myself to put the bins out. I’ve discovered that meditation is just something that not everyone can do, in the conventional way at least.

The other day I went to Rye Meads Nature Reserve in Ware, Hertfordshire. I have quite a lot of things to do at the moment with my MA and the move to Scotland later this month, but I needed some time outside. I find it a real challenge to make time for walks, so I fought my better judgement and put work on hold to sit in a hide and watch birds. I don’t do this much – when I’m out and about I’m either on my way somewhere or keeping an eye on the dog to make sure she’s not getting into mischief, so it was a real indulgence to spend an entire morning ambling around a nature reserve.

I sampled each hide in turn, following muntjac prints in the mud as I walked, and eventually settled in one that overlooked a lake speckled with birds. A group of thirty lapwings were soaring over the water, swinging in a single mass from left to right. Each time they twisted the sunlight caught their backs, illuminating that iridescent green also concealed in magpies and starlings. I watched their display through the binoculars, captivated by the pendulum-like movement. Unlike a lot of wings that end in sharp points, these birds have wings that are loosely shaped like tennis rackets.

Eventually one bold individual decided that was quite enough flying, and as it swooped down to the water its companions followed until the air was empty again. They settled on the rocks alongside a pair of shelducks, shovelers, gadwall and a lone cormorant. The strips of pebbles cut the lake into wedges, separating midnight blue from slate grey. Ripples from bobbing coots sent tiny waves onto the shingle.

“Have you seen the green sandpiper?”

The voice made me jump after such a long silence. It was a member of RSPB staff, brandishing both binoculars and an impressive scope. Shimmying along the bench, I peered down the scope and watched the wader as it scoured the shingle for food on its skinny green legs. I’d have never spotted such a well-camouflaged bird without help. In fact, the green sandpiper was a species that I may have looked at but not noticed many times before.

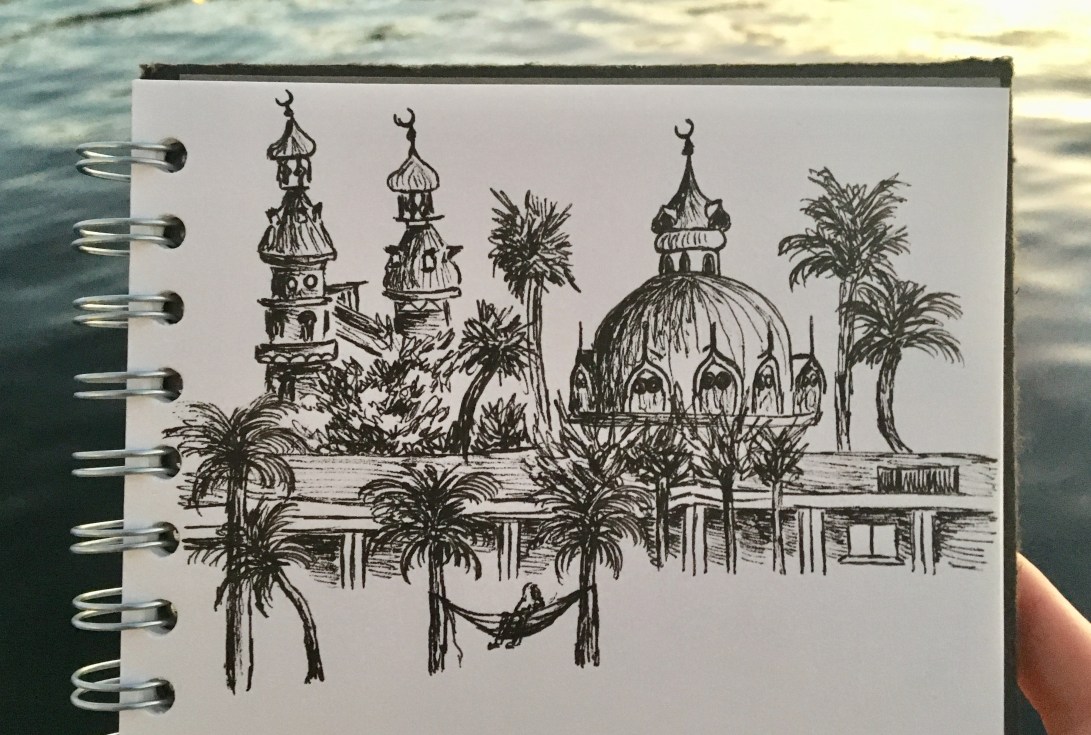

The man with the scope carefully lowered the window cover and hitched the scope onto his back, heading back out into the sunshine. I carried on watching the lapwings, now foraging with their spiky hairdos fluttering. It occurred to me then that birdwatching was a form of meditation. You have to sit still, as quietly as possible, and often go for hours without speaking. My phone was on silent, buried at the bottom of my bag underneath gloves, sketchbooks and biros. The only connection I had was with the birds. Sure, I was hoping for bitterns, kingfishers and otters (none of which showed), but I found satisfaction in the more common residents. There is undeniable beauty in a young blue tit’s downy feathers, the tight curl of a cormorant’s dive and the vibrancy of a mallard drake’s head, which almost shines yellow in the right light. Maybe I’d denied myself the pleasure of birdwatching too long, but sitting in the hide looking out onto calm water felt like meditating. My work was back at the house and I was in the reserve sharing space with birds.