Last weekend I stayed with my grandmother at her lovely house in Frome, Somerset. I love my mini holidays there; my bedroom window overlooks a meandering river, and on the other side is a bustling market and a glimpse of the library through the overhanging trees. I was particularly excited on Saturday morning to discover there was a Christmas fair in full swing. There’s nothing like a fair in late November to get you in the mood for Christmas. Although I still refuse to play festive music before December, a sprinkling of Christmas spirit is more than welcome, especially in such bitterly cold weather.

Once inside, we joined the throng. Shoppers shuffled along tables laden with all sorts of gifts and bric-a-brac. The Cats’ Protection were selling cat-themed stationary, while a young man at the Somerset Wildlife Trust stand was doing his best to sell membership to a middle-aged woman whose attention was slowly waning. I am a firm supporter of the Wildlife Trusts, but membership recruiters have a way of pulling you in for a short (thirty minute) chat and not letting go. Past experience taught me to avoid his gaze, and I spotted the table I’m always searching for: the one covered in books.

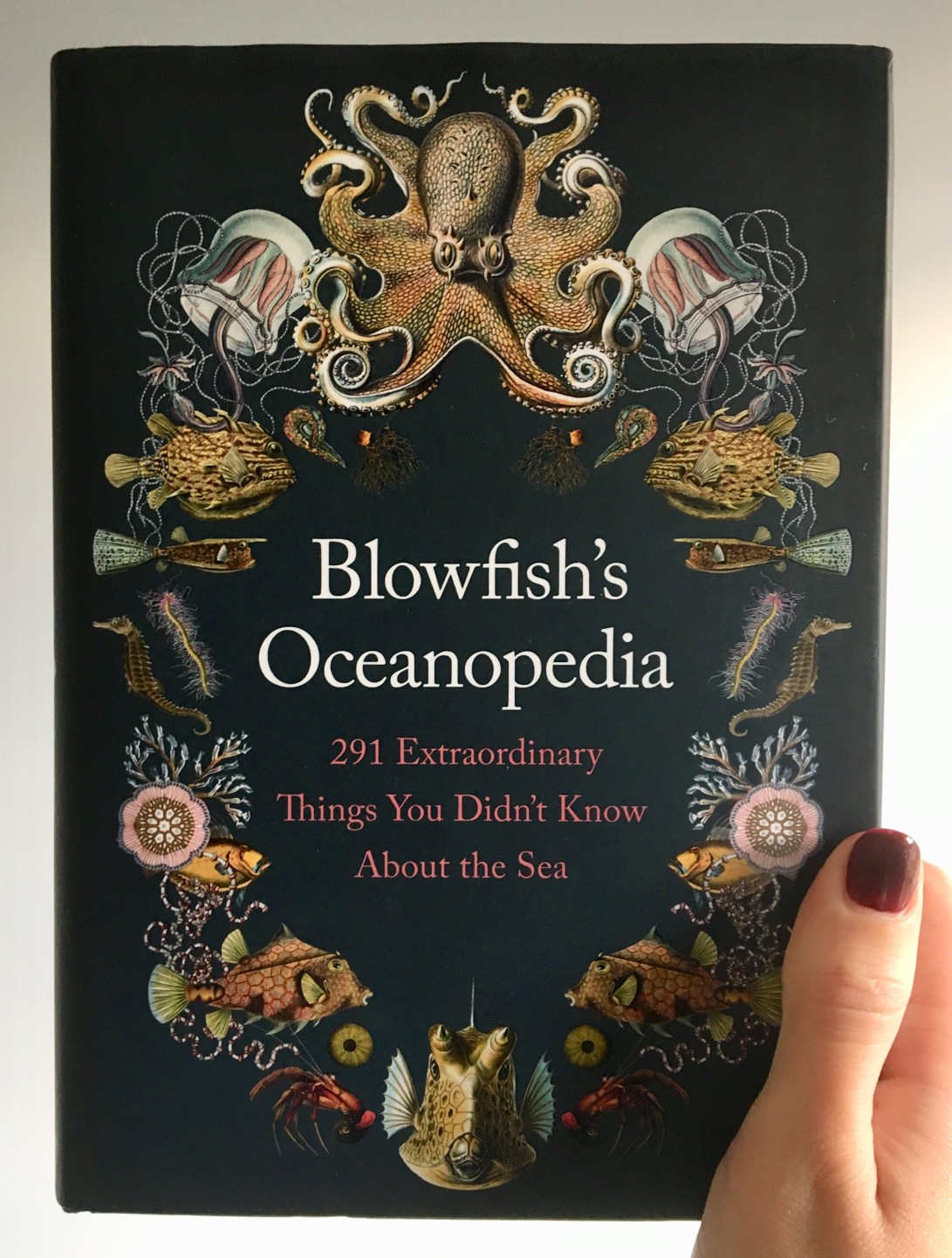

As always, there was a decent selection of dog-eared Maeve Binchy and Danielle Steel paperbacks, but amongst covers showing watercolour landscapes and female silhouettes staring wistfully into the distance was the tail of a fish. I tugged at the fish and my eyes fell on beautiful line drawings of an octopus, jellyfish, seahorses and more. It was such a satisfying cover, and the book was called “Blowfish’s Oceanopedia”. It was one of those dip-in books with titbit information: “extraordinary things you didn’t know about the sea”, it said. As a person who is fascinated by the sea but doesn’t really know anything worthwhile about it, it seemed the perfect read for me.

The price was even better. A brand new book, published last year at £17.99, and I was charged a pound for it. Books were amazing, but books for a pound were magical.

After finishing my loop of the fair – and winning a raffle Christmas present in the process – I returned to my grandmother’s house and instantly curled up in my favourite chair to begin reading. Within minutes I’d learned a decent thing or two about elephant seals. I am quite terrified of elephant seals, but as with my similar unease towards snakes and sharks, I’m also fascinated by them. The Blowfish revealed just how important the southern elephant seal’s “trunk” was to its survival. During the breeding season, males weighing up to 4 tonnes battle it out to win ownership of the harem of females. Understandably, this is a full time job, and prevents males from returning to the water to feed and drink. So, to avoid dangerous dehydration, males use the complex nasal passages and specialised blood vessels in their fleshy trunks to recover around 70% of the water vapour in their exhaled air. It’s a genius example of life-saving recycling.

This is the sort of book I dream of someday replicating; an instrument to share my knowledge and passion with like-minded people. At the moment I’m not an expert in any one field, but the idea of spending decades of your life learning about something and then teaching others in the form of writing is, to me, the perfect way to preserve your work.

The Blowfish, also known as Tom Hird, is a marine biologist who has a deep love for the ocean and life within it. He’s the perfect voice for a potentially complex subject matter, using humour and everyday situations to diffuse a tricky concept. Speaking in the same language as the layman is something some scientists find extremely challenging. I’m certainly not a marine biologist, but nor am I completely naïve to the science of the natural world, so I often feel my combination of knowledge gives me an advantage. I can understand a lot (not all) of what scientists do, but I also appreciate how that needs to be adapted to inform the public without dumbing down and insulting them. I’m sure there are hundreds of published papers on the adaptations of southern elephant seals which required many hours of hard work, but to the average Joe wanting to find out something interesting about wildlife, a book like the Blowfish’s will be a much bigger success. I believe the key to nature writing, or any writing for that matter, is finding the balance between informing and entertaining. The Blowfish’s Oceanopedia has been a source of great inspiration to me – a writer hoping to one day publish books of my own. The passion and enthusiasm in the author’s prose is infectious, and makes me want to jump in the sea right now and see for myself everything he has had the opportunity to witness.