After a busy week getting to grips with my new routine in Florida and getting stuck into all sorts of exciting work at the SEZARC lab, I was invited onto a tour of the White Oak site. Having only had glimpses up until now – mainly the white rhinos whose enclosure runs alongside the road to the lab – I was eager to see all of the animals that live at White Oak.

Our first stop was the greater one-horned rhino, and I was thrilled to see one of the females had a calf. The clue to the most immediate difference between these individuals and white rhinos was in the name; white rhinos, from Africa, have one more horn than the greater one horned, and they’re typically larger. To compensate for a shorter horn, these rhinos – from India and Nepal – have very long lower incisors that are used during fights and can grow up to 8cm long in males.

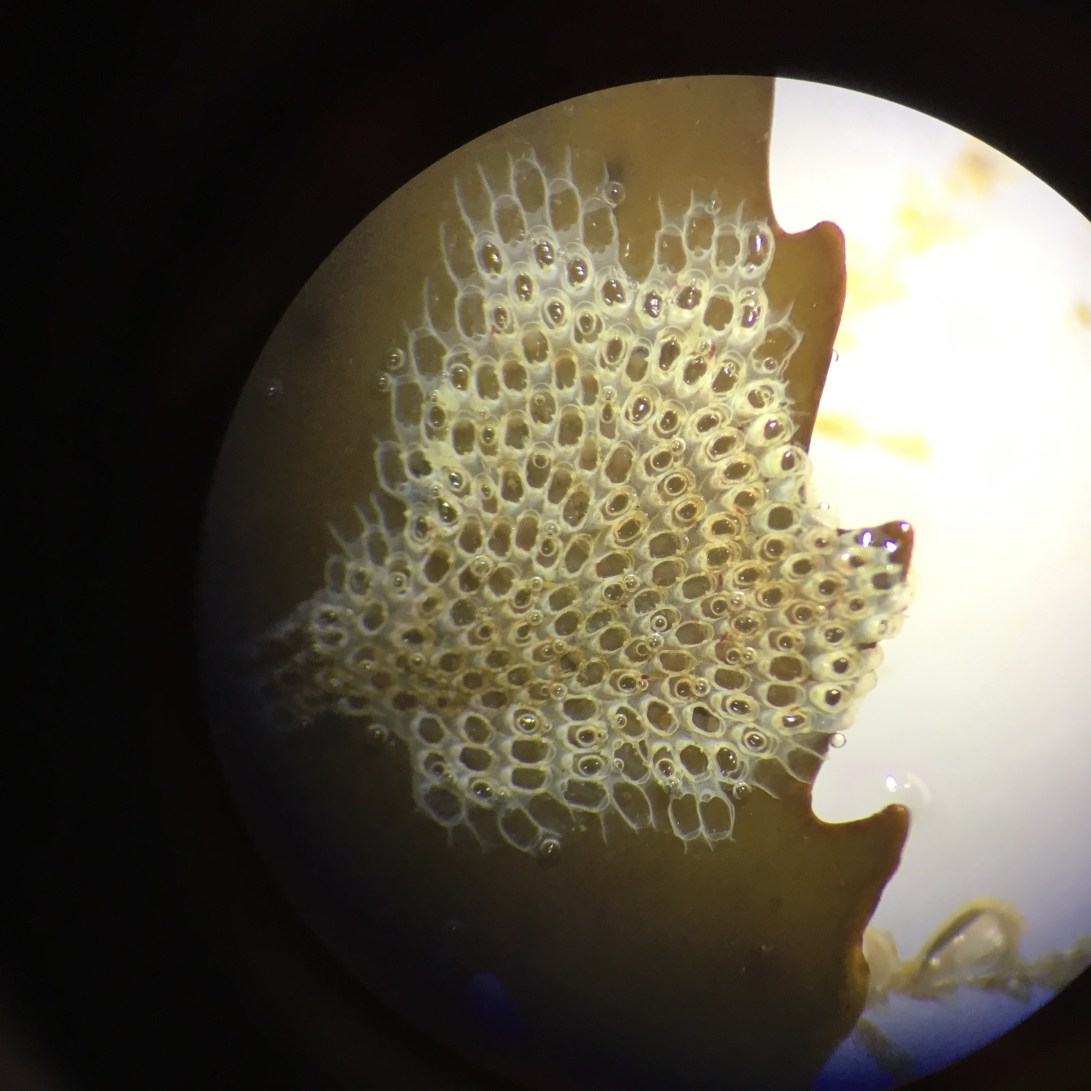

The armour-like skin gives these rhinos the appearance of a prehistoric creature. It is deeply folded to increase the surface area for water absorption, and especially thick around the neck to protect this vulnerable area. Greater one-horned rhinos have a prehensile lip that they use to forage in scrub and foliage.

White rhinos, on the other hand, are known as square-lipped rhinos and shed grass like a lawnmower. As we watched them graze we saw they were surrounded by cattle egrets, a common sight at White Oak. These white, gangly birds follow large mammals around their enclosures, as their weighty footsteps disturb insects hidden in the ground below, which the egrets take full advantage of.

Next we headed off to find the Somali wild ass, a species I had never heard of but fell completely in love with. Found in East Africa, Somali wild ass are the smallest and also the rarest wild horses (equids) in the world, with fewer than 2000 left in the wild. They have a beautiful grey coat that almost appears purple in a certain light. Reminiscent of their relative the zebra, these wild ass have characteristically striped legs. Due to competition with domestic farm animals for grass and water, these animals have become critically endangered. In response, White Oak obtained a herd in 2008, and since then have raised twenty foals.

Nearby to the Somali wild ass was another species I hadn’t come across before: the gerenuk, meaning “giraffe-necked” in Somali. These slender antelope are golden in colour with extraordinarily large necks, ears and eyes. Interestingly, these antelope rear up onto their hind legs to get to even higher places.

One of the final stops on our tour was an unforgettable moment for me: the giraffes. I’ve always had a soft spot for giraffes, and today I had the extraordinary surprise of being told I could hand-feed one. His name was Griffin, and as soon as the bus stopped he came striding over, keenly peering in through the window. One by one, we took a piece of browse and lifted it high, and Griffin gently took it. It was such a treat and a moment I will treasure for a long time.

As we got back onto the bus and made our bumpy way back to the car park, I felt honoured to have seen first-hand what an amazing place White Oak is for conserving and protecting wildlife. While I commend many zoos for their conservation work, I was so pleased with how much space these animals had, giving them the freedom to behave as naturally as possible. It made me so excited to continue my internship and I looked forward to getting even more involved as the weeks progress.